Fiorucci made me hardcore

Mark Leckey

1964, Birkenhead (United Kingdom)

Lives and works in London (United Kingdom)

Fiorucci made me hardcore, 1999

Betacam SP analog video tape, digitized

4:3, color, mono sound

15 min.

Purchase, 2002

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne - Centre de création industrielle (Mnam-CCI)

AM 2002-126

Since the late 1990s, the work of British artist Mark Leckey has focused on the relationship between popular culture and technology, exploring ideas of youth, social class and nostalgia through sculpture, film, sound and performance.

In Fiorucci made me hardcore, Leckey spliced together archival footage from British dance halls and clubs, chronicling underground dance music in England from Northern Soul in the 1970s to rave in the early 1990s. An expert on club culture, he reveals how many followers of these musical genres adopted certain clothing brands as rallying signs. His sampling and editing of this footage anticipate the manipulation of digital sources by the YouTube generation. The video evokes nostalgia for a recent past now out of reach, and also demonstrates an obsession with the archive that is central to the artist's work: “I’m a fetishist and I fetishise things,” he says. “I'm drawn to these things and I'm obsessed by them, I have to somehow possess them, because I sense that they possess me. I want a form of reciprocity.” To complement this visual montage, Leckey created sound from a variety of sources, which he then transformed and associated with the appropriated images. Epochs are blended together as visual and audio documents are cross-fertilised to create a timeless whole.

- Read more about Fiorucci made me hardcore

- Log in or register to post comments

Mark Leckey

<It was so quiet that the pins dropped could be heard…>

Ye Hui

1981, Canton (China)

Lives and works in Vienna (Austria)

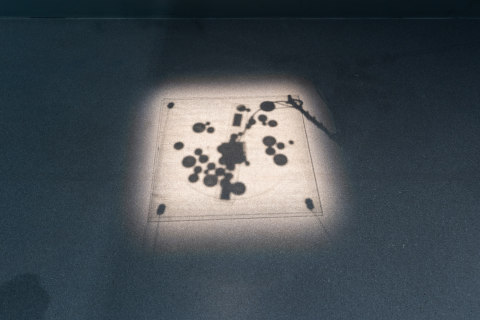

It was so quiet that the pins dropped could be heard…, 2011

Plexiglass plates, pins, magnets, motor, mini glass bottles

Courtesy of the artist

As a sound artist, Ye Hui uses a variety of media (installation, performance, video) to question the social identity of the individual and its entanglement with different cultural and political contexts. Her work focuses on the socio-political aspects of the act of listening, exploring the connections between sound and various social phenomena in contemporary societies.

In this installation, Ye Hui used a rotating motor to move magnets attached to an acrylic glass bar. Pharmaceutical bottles filled with pins are placed on the underside of an acrylic panel. The movement of the magnets briefly pulls the pins upwards before they fall back to the bottom of the glass bottles, creating a gentle percussive sound. As the title suggests, It was so quiet that the pins dropped could be heard... requires attentive listening and quiet reception on the part of visitors if they are to perceive the full subtlety of the sounds generated by the work. The artist, explaining the origin of her project, states: “The installation was inspired by the idiomatic expression 静可闻针, which specifies a listening situation within absolute quietness so one could even hear a pin drop. On the other hand, such kind of quietness probably only exists in one's imagination and the idioms 静可闻针 is indeed the description of a (collective) perception of not only acoustic, but also psychological condition. Therefore, the installation can be understood as the physical amplification of the linguistic/idiomatic expression 静可闻针.”

- Read more about

- Log in or register to post comments

Ear to the Ground

Kit Fitzgerald

1953, Springfield (United States)

Lives and works in New York (United States)

John Sanborn

1954, Huntington (United States)

Lives and works in New York (United States)

Ear to the Ground, 1981-1982

Umatic 3/4 inch NTSC videotape, digitized

4:3, color, sound

4 min. 50 sec.

Purchase, 1985

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d’art moderne - Centre de création industrielle (Mnam-CCI)

AM 1985-441

Kit Fitzgerald and John Sanborn belong to a generation of video art pioneers on the New York scene in the 1970s, who were attracted to the South Korean artist Nam June Paik. Inspired by Paik’s hybridisation and anti-art stance, these two American artists developed their own work while also engaging in dialogue with choreographers and musicians to forge new links between different art forms.

Between 1976 and 1982, Fitzgerald and Sanborn worked as a team to explore the relationships between music, performance and video-editing techniques in the New York underground networks of the time. In Ear to the Ground, the duo filmed experimental percussionist David Van Tieghem – whom Sanborn had met on an evening at the Kitchen, a renowned alternative programming space dedicated to performance and video – on the streets of New York.

Armed with two drumsticks, Van Tieghem brought a new rhythm to the streets of Soho and Tribeca, giving a sonic function to the urban objects he encountered: pavements, walls, pipes, iron curtains, telephone boxes and asphalt. This entirely improvised performance adopted the principles of European musique concrète, focusing on the ordinary sounds of the city rather than those produced by more conventional instruments. The work asserts its lightness as an ephemeral gesture, ultimately restoring its own sonorities to the city.

- Read more about Ear to the Ground

- Log in or register to post comments

John Sanborn

Kit Fitzgerald

In a sense that yet to be made : Acoustic Explorations and Interpretations in China

Over the past two decades, sound art in China has experienced a creative revival that touches on a number of themes: the tension between the audible and the inaudible; the relationship between acoustic vibrations and the environment; and the socio-political dimension of the act of listening. At the same time, these practices represent a meeting point between different artistic cultures, with musicians taking over the installation or visual artists using sound to compose works while proposing original images or graphic works to accompany their productions. Numerous formal and conceptual innovations have thus created a new relationship with auditory attention in accordance with the specificity of the artists. As a result, their works are now circulating around the world in various forms. Initially, this took the form of compilations such as China: The Sonic Avant-Garde [Fig. 1], produced in 2003 by the label Post-Concrete, founded in 1997 by Dajuin Yao, a professor, curator and artist at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, to promote Chinese sound art on a global scale . In addition, festivals such as “Sounding Beijing: International Electronic Music Festival” (The Loft New Media Art Space, Beijing, 1-4 November 2003), the first international sound and new media event in China, brought together Chinese and Western artists. It took place three years after the first part of “Sound” (Contemporary Art Museum in Beijing, 2000), a group exhibition conceived at the initiative of curator and artist Li Zhenhua, which marked the public recognition of sound as an artistic medium in mainland China at “a time when neither Western theories of sound nor institutional models of sound art as an independent genre were available to the mainland art world ”, according to researcher Jing Wang, associate professor of sound studies and art anthropology at Zhejiang University (Hangzhou). And since 2013, the exhibition series “Sound Art China: Revolutions per Minute” – the subject of another compilation – has continued to highlight Chinese sonic creations abroad (notably in New York ), but also in Shanghai and Hong Kong. This project, developed by Dajuin Yao, whose activities at the China Academy of Art (a participatory sound art programme, festivals, exhibitions…) have contributed to promoting the Chinese scene, is also developing on the fringes of cultural institutions, as demonstrated by the recent festival “A Bunch of Noise”, the first edition of which took place in Shanghai in 2023, bringing together a radical generation of “noise” artists [Fig. 2].

These various references testify to the importance of a diverse scene made up of many creators, some of whom are prominently featured in the exhibition “I Never Dream Otherwise than Awake: Journeys in Sound”, including Wang Changcun, Hui Ye, Sun Wei and Samson Young. The multiple universes of these artists show how outdated the all-encompassing term “sound art”, which is often used to lump them together in a rather hasty Western reading of their work, has become. All the limitations of this concept become apparent when we consider the artistic categories presented by Jing Wang in his book Half Sound, Half Philosophy: “sound installations, sound in performance-oriented conceptual art, sound machines/object installations, public sound art, and sound and net art ”. Although they are not exhaustive and may overlap in the work of certain artists, these variations clearly underscore the richness of the mediums used. In his article “Sound Art in China: Revolutions per Minute”, Dajuin Yao also questions the term “sound art” and its Western definition: in his view, this term differs from “cultural listening” in China, which draws on an ancient interpretive tradition that emphasises multidisciplinarity. Yao points out that “the Chinese interest in sound has never been in the sounds themselves or acoustics, but in their correlations, references, and the interplay of phenomena. Sound, music, and tuning have been correlated to cosmology, astronomy, astrology, philosophy, medicine, and so forth ”. While Western sound art can be traced back to a modern tradition firmly rooted in an official art history – the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo’s The Art of Noises (1913) comes to mind, as do the sonic explorations of pioneering artists such as John Cage, Max Neuhaus, Alvin Lucier and Bill Fontana – Yao’s approach links contemporary Chinese sound art to a cultural phenomenon that is “an extension of one of the oldest and most important heritages in world auditory culture ”. However, a new generation of artists is attempting to mitigate this comparison through the lens of humour: Yan Jun, a poet, musician and independent curator, ironically describes Chinese experimental music as “loser’s music ”, as theorist Jing Wang reminds us. In the 2017 compilation There is no music from China [Fig. 3], created with the musician and promoter Zhu Wenbo, and in the 2020 compilation Music will ruin everything, Yan Jun presents “a humorous negation of categorical identities of the national and the musical ” both in the compositions of the pieces and in their titles. However, these initiatives can be seen as part of Chinese listening culture, albeit a small part. According to Jing Wang, its origins lie in the philosophical concept of qi: “In ancient China, qi was considered both the vital source breath for life and the driving force in the cosmic world. Qi was used to describe the human body as used in qi-blood, explaining how the human is a part of the resonant cosmic cycle, forming into a union with the heaven and earth. The notion of qi refers to the ceaseless fluctuation, interpenetration, and transformation of yin-qi and yang-qi. Through different historical periods, qi, from a vague idea, was developed into a cosmological, aesthetic, social, medical, moral concept, and eventually a philosophical system, reaching its maturity in the Song Dynasty ”.

The complex origins of sound creation on the contemporary Chinese scene reveal a subtle balance between traditional and electronic culture. This relationship can be seen in Dajuin Yao’s installation Geophone Nanking (2005), which recreates a military surveillance device used during battles in China two thousand years ago, but also in Yan Jun’s work in his performance How to Eat Sunflower Seeds (2011-2013), an exploration of popular culture, and in Seeds Dialogue [Figures 4 and 5], “a quadraphonic installation playing back the sound of four persons cracking sunflower seeds, a popular Chinese snack and pastime, as if in a conversation ”. Using the fabric of everyday life as a medium, Yan Jun has developed a novel approach to sound performance – a language, which, for Dajuin Yao, “has always been the core and soul of Chinese culture. Acoustically speaking, for artists using language as sound samples for signal processing, the Chinese language family, being tonal (words sharing the same sound are differentiable only through pitch variations) and with numerous dialects and regional variations, offers a tremendously rich resource for all types of experimentation in digital signal processing and modulation ”. While some artists make language the central medium of their work, other musicians are exploring new ways of communicating, such as Samson Young, who proposes new protocols for performing classical music repertoires. In his piece Muted Situation #22: Muted Tchaikovsky’s 5th (2018), the sounds of the instruments used to play Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 are suppressed to make way for a new sonic environment in which only the gestures of the performers, at one with their instruments and their scores, are audible. In this silent version, this classical work is deconstructed to create a political object that reveals the efforts of each member of the orchestra. This unveiling of the imperceptible takes other forms in the artist’s work. Art historian Alenka Gregorič, describing the video Sonata for Smoke (2021) [Fig. 6], which “focuses on the ordinarily invisible instruments used in creating video and film, thereby showing how the sound of a performing body is recorded”, explains that Samson Young “invite[s] the viewer to closely observe sound as an intensely present element, [and] shifts our focus from the visible to the invisible, from the obvious and self-evident to a search for the origins of soundscapes. Sonata for Smoke is both a recording of sound and a creation of a new image in which image is subordinated to sound ”. This link between sound and image manifests itself in a cross-fertilisation of artistic cultures, as Samson Young, who is trained in musical composition, covers a wide range of practices in his work: performance, sound, video and drawing.

This phenomenon of hybridisation can also be found in the work of many Chinese artists living in mainland China and abroad. In this respect, the musician Pan Daijing also embraces a variety of disciplines, striving to renew the codes of performance in addition to her compositions and concerts. This is particularly true of In Service of a Song (2017), in which she invites the audience to experiment with the possibilities of sonic imagination [Fig. 7]. Four improvised performances of thirteen minutes each took place on consecutive days in a transparent, soundproof box at the House of World Cultures in Berlin. Pan Daijing shared this box, a structure surrounded and filled with earth up to the ankles, with several sculptures, gymnastic rings and her pet turtle, the only other living organism to witness the performance from inside. In the second phase, the work was transformed into an exhibition, in which a four-channel video recording of the event was presented alongside the sculptural installation, extending the meaning of the performance into the space of the Isabella Bortolozzi gallery in Berlin. In Service of a Song sought to liberate the listening experience by inviting the audience to focus on their own auditory imagination, while proposing a new representation of the figure of the musician through performance. This approach feeds into a segment of the Chinese electronic music scene, most notably represented by Menghan Wang, Wei Wei (aka Vavabond) and Torturing Nurse , in whose work harsh noises interact directly with the artists’ bodies, in sonic landscapes that reflect the hyper-industrialised world of contemporary China. Suffused by an abundance of urban sounds, from subway muzak to smartphone alerts, the frequencies of China’s over-connected society are being appropriated by a new wave of visual artists and performers sensitive to this diffuse sonic influence. While the China Sound Unit collective had begun to address the growing importance of mobile phones in users’ daily lives in the late 1990s, iPhones quickly became the target of Chinese composers. In 2012, Wang Changcun, a member of the collective who is adept at field recording, created a sound art app for smartphones called Cicadas, which generates the synthesised sound of cicadas that users can modulate at will. Subverted from its original function, the smartphone proposed a new connection with nature, gradually being eroded by the hegemony of technology and the constant noise of the global city. This object made it possible to move from the discomfort of hearing to an unexpected state of acoustic comfort, establishing a new relationship with listening and encouraging creative minds to examine sound in a different way.

Captions

Fig. 1 – Compilation China: The Sonic Avant-Garde, Berkeley (CA), Post Concrete, 2005, compact disc.

Fig. 2 – “A Bunch of Noise” festival poster at System, Shanghai, 4 April, 2024. Artwork by Shuangfa Dong.

Fig. 3 – Compilation There is No Music from China, Beijing, Zoomin’ Night / Christchurch (New Zealand), End of the Alphabet Records, 2017, audiocassette.

Fig. 4 – Yan Jun, score of Seeds Dialogue, page 3 of 12, March 2010.

Fig. 5 – Yan Jun, How to Eat Sunflower Seeds, August 2011, Beijing, Today Art Museum. Photo by Yan Jun.

Fig. 6 – Samson Young, Sonata for Smoke, 2021 (revised), video with stereo sound, 15 minutes 49 seconds, pastel on recycled paper, pastel on acrylic, pastel on air-dry clay. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Dennis Man Wing Leung.

Fig. 7 – Pan Daijing, In Service of a Song, 2017. Installation views, House of World Cultures, Berlin.

Open Score: Listening to an Exhibition

Since the beginnings of modernism, sound has shaken up the norms of the history of art, expanding them and introducing a new level of complexity. This exhibition highlights the renewed fecundity of these exchanges over the last twenty years. Moving beyond the notions of audio art or sound art as coined in the 1970s , it assembles a wider range of artistic trajectories and cultures, while also taking into account the articulations between experimental music and exhibition spaces that have become increasingly visible in China in recent decades . Bringing together works from the Centre Pompidou’s collection and those of artists and musicians working in China, the exhibition brings to light a constellation of research that explores the expressive possibilities of sound in both its perceptual and conceptual dimensions. A key aspect of sound’s expressiveness lies in its ability to occupy space and spread in various ways – the displacement and ubiquity of listening, one might say – in connection with contemporary media. Sound is inherently fluid and invasive; the ear has no eyelids. The ways in which it is addressed and disseminated in contemporary contexts, media and devices are critically examined here.

The exhibition begins with several historical artists who explored these issues in the twentieth century through sound installations and experimental videos. Echoing these pioneering works, the propositions being developed today are the fruit of cultures that rarely confine themselves to a single mode of expression. Artists often move from concert to installation, from musical composition to technological research and to the creation of new visual languages. Improvisation protocols and collective cultures, field recording, sampling and collage, feedback and filtering, algorithmic generation and creation through social networks are all significant gestures in embracing a changing relationship with the world. The title of the exhibition, “I Never Dream Otherwise than Awake”, is borrowed from Emmanuel Lagarrigue, whose eponymous work from 2006 is presented as a choral landscape to be explored. Evoking a state of daydreaming, this statement is both a personal revelation and an invitation to examine the conditions of perception beyond convention and habit. It suggests a back-and-forth between wakefulness and sleep, between the lucid perception of the here and now and the free flow of dream work, where a semi-conscious state of research can begin, pointing to representations yet to come.

Here and There

The exhibition opens in the public space around the West Bund Museum and its atrium. Bill Fontana, Susan Philipsz and Sun Wei: three generations of artists who renew the idea of sound sculpture and give it multiple resonances. While their works structure the experience of space through auditory perception, they also create a layered, complex sense of time, providing material for future narratives. Bill Fontana, who studied with John Cage in the late 1960s, developed a specific form of sound sculpture in which sound is captured and relocated, moved from one place to another, profoundly altering the processes of perception and interpretation that combine sight and sound. Since the mid-1990s, Susan Philipsz has been interested in the connections between listening and memory, both individual and collective. Presenting a traditional folk song in her own non-professional voice, her work The Cuckoo’s Nest reminds us that the spatialisation of music, a characteristic of experimental research in the twentieth century, was already present in vernacular forms in the polyphonic art of the Middle Ages. Combining field recording, sampling and experimental electronics, Sun Wei composes with sound materials in the same way that one might shape a landscape to reconcile nature and artifice. His installation Sound Temple brings an echo of the sounds of the world into the museum. Sounds that he records or finds – including on the internet – are processed from a precise acoustic perspective, based on the frequencies conducive to meditation encouraged by the architecture of temples.

At first glance, these works seem to have a singular relationship to the architectural space, to the point of creating a specific place and situation where one is invited to take one’s place, so to speak. However, their sonorities also take us elsewhere, inviting and superimposing sonic realities from other places. These require a second hearing, heightened attention and clarity. At once here and there, in the present and in the long sweep of history, the echoes between distant places come together in unexpected musical configurations.

Thresholds of Listening

If listening is linked to proprioception, the awareness of one’s own body in space, the three works in this second section of the exhibition play with the limits of this sensory state, focusing on discrete, delicate sounds, sometimes on the edge of audibility. The installation by Edmond Couchot and Michel Bret bears witness to their pioneering experiments in computer interactivity between sound signals and digital animation. Only the frequencies of breath – picked up by a microphone made available to the public – gently set the visual representation in motion. The works by Emmanuel Lagarrigue and Hui Ye demand a state of active concentration, requiring one to strain one’s ears and get as close as possible to the source of the sound. The first takes the form of a journey in which Lagarrigue confronts the audience with an ocean of murmurs, made up of the fragile humming voices of amateurs singing their favourite songs. The second is a transparent motorised sculpture whose rotation amplifies random sounds. With gentle irony, Hui Ye attempts a literal representation of an abstract idiom: “It was so quiet that the pins dropped could be heard…”. Each of these works explores, in its own way, the gap between the regime of language and that of sensory experience.

Listening can be atomic, molecular; a micro-event in sound produces unexpected feedback and unsuspected vibrations. It is interesting to note that the eardrum is the most archaic remnant of the human organism, bearing witness to a pre-human sensory system that predates the rational operations of consciousness. The works presented here reveal the very experience of listening and the mechanisms of empathy that it evokes.

Sound and Sight

The perfect synchronisation of image and sound, achieved by cinematic technology at the turn of the 1930s and reformulated three decades later by the electronic signal in the medium of video, has given rise to a great deal of artistic experimentation. The three artists in dialogue in this section analyse and challenge the analogue technologies that coordinate sight and sound. In a seminal video from the 1970s, Gary Hill appropriates one of the first tools for the electronic visualisation of sound – the sine-wave oscillator – in a performance that illustrates how difficult it can be to combine the human organism to cooperate with the capabilities of the machine to enable a translation between sound and image. Wang Changcun pays homage to the “static sound” of cathode-ray tube television, which he juxtaposes with a field recording of a waterfall. By proposing a kind of “trompe l’oreille” (literally, ‘tricking the ear’) in which the sound information is misinterpreted as the equivalent of snow on television screens, his installation invites us to free ourselves from the assumption of veracity usually ascribed to sound images. In addition, Changcun suggests that sound and image transmit largely unknown frequency fields in which everything remains potentially legible and decipherable. Oliver Beer takes one of the masterpieces of synaesthesia, Snow White (1937), Walt Disney’s first full-length animated feature with sound, and shatters its unity by delegating its recreation to a group of children.

Each visitor will experience the contrasts, gaps and ruptures between the audible and the visible. The aim is to test a new axiom, with sound and image meeting in the poetic indiscipline of senses and ideas. Sensory memory can be deceptive; it leaves room for fertile disjunctions.

Diverting the Instrumentarium

Since the advent of the avant-garde in the twentieth century, the growing interest of visual artists in music has also led to the emergence of numerous works aimed at expanding the range of instruments: the modification or appropriation of the classical Western instrumentarium, as well as the conception or transformation of novel instruments – the artistic inventiveness in this field is limitless. These new resonant objects challenge, destabilise or redefine the boundaries of what is typically perceived as the “musical” character of sound. As early as 1913, Luigi Russolo's manifesto The Art of Noises proposed a musical approach to the soundscape of the urban environment. Russolo elevated the status of a vast array of noises, with the idea of transforming them into new timbres of musical sound. In the 1950s, John Cage proposed that all sounds deserve equal attention, shifting the focus of music towards active listening. The three contemporary artists featured in this section extend such conceptual shifts, by working with new materials and sonic situations whose primary quality is disruption. Yuko Mohri’s work constitutes an automated fanfare of found objects that subtly exude a sense of rebellious poetry infused with the absurd. Challenging the technicity of the musical game, Naama Tsabar has designed a double electric guitar that forces performers into an improvised collaboration, subtly distancing itself from the stereotype of the heroic solo associated with this instrument in rock music. In his series Muted Situations, Samson Young renders the sound of an entire symphony orchestra unrecognisable by removing the vibration of the instruments, the substratum of Romantic music that this vast ensemble was originally intended to elevate.

The term “sound object”, coined by Pierre Schaeffer in the 1950s, has taken on two semantic meanings over time. In one sense, it denotes an isolated sonic phenomenon perceived as a unit, whether musical or not . In another sense, it has gradually come to describe a wide range of material objects that artists, from Fluxus performances to contemporary installations, imbue with sonic intentionality and operativity. Such gestures shift the boundaries of the musical domain, challenging the cultural, social and political value systems attached to it in any given context.

Urban Wanderings

The history of how we hear is inextricably linked to the mapping of sound. As a place of constant human flow and interaction, the city is imbued with its own distinctive sonic identity. It is, by definition, a heterogeneous environment made up of overlaps, intersections and encounters. Whether chosen or conditioned by the vagaries of the economy, urban wandering represents a displacement that is both tangible and emotional, anonymous and intimately experienced. Through the medium of sound, Francis Alÿs, Zhou Tao and Emeka Ogboh address the often invisible realities that shape our experience of the city, a bustling territory of dense and fluctuating occupation, frequently contrasted with the peaceful and tranquil sedentariness of the countryside. In his video, shot in the streets of Venice, Francis Alÿs presents the performance of a conceptual duo for solo trombone. In this winding urban labyrinth, wandering becomes a poetic act in which the playful logic of chance takes precedence over the imperatives of productivity. Also a performance, Zhou Tao's work brings the sounds of rural life into the heart of a contemporary Chinese metropolis. Between centre and periphery, day and night, audible and inaudible, these polarities are transformed. Emeka Ogboh’s diptych of sound paintings brings the echo of the ever-present sounds of Lagos into the exhibition space. The work plays with an apparent formal abstraction, revealing through intermittent sounds references to the daily transit of Nigeria’s border populations.

Each of these three propositions contrasts in its own way with the tumult of the city, creating the conditions for a singular auditory event. A distinct, identified sound then emerges like a semaphore, directing our attention to rethink or reinvent our perception of the urban landscape.

Frequencies of Trance

The metropolis is also home to an increasingly effective internationalisation of music production. Since the 1990s, electronic music, driven by the record industry, has been the cultural flagship of globalisation. By absorbing spontaneous forms of working-class expression into a mass economy, it has established new rites of belonging and new forms of community across the globe . The two audio-visual installations dialogue with one another in this section examine the globalised musical ethos from the perspective of the vernacular through a subtle use of fiction. The respective soundtracks, charged with intense rhythmic parts, anchor imaginary scenes in which an interference of times unfolds. In a liminal space reminiscent of the seabed or a celestial vault, Hassan Khan creates a stirring dance, tinged with strangeness, to the sounds of electro chaâbi. This Egyptian musical genre is a contemporary version of traditional chaâbi music , reimagined through a lens of heightened electronic saturation. It is very popular and crosses all social classes, from the streets to discotheques and even private wedding parties. Khan composed the music and choreography himself, turning his work into an allegorical portrait of society. Liu Chuang interweaves two musical stories in a science fiction scenario, one celebrating the timeless beauty of the songs of Western China, and the other depicting the invasion of Western pop music in Hong Kong in the 1980s. Making references to ethnomusicological methods, he creates a fantastical narrative with a hypnotic quality, enhanced by the fact that it is broadcast from a psychedelic hi-fi cabinet, built at the turn of the millennium to recreate the atmosphere of a discotheque on a domestic scale.

In the conceptual practices of these artists, the borrowing of musical forms that induce deep or altered states of consciousness opens up a vast mental space of representation.

The Proxy Voice

The last two sections of this exhibition examine the influence of digital technologies on social practices associated with sound, music and listening in greater detail. These technologies facilitate and legitimise the complete disembodiment of individual expression in many ways. In telecommunications, the term “proxy voice” describes a system of encryption that conceals the identity of both the sender and the receiver. In psychoanalysis, it is understood as a technique whereby the therapist borrows the patient’s voice in order to facilitate the release of blockages. Once regarded as the most direct means of expression and the most authentic indicator of one’s individuality, the voice can now be delegated, and becomes an indirect means of expressing personality. It is this troubling phenomenon that the artist Anne Le Troter explores. After collecting messages from sperm bank donors, she staged a vocal choreography that demonstrates the distance between the body and its anonymised voice, which is mediated by an online platform. In this context, stereotypes emerge in the form of rhymes and repetitions, raising the question of who is articulating such homogeneous desires.

In some ways, ventriloquism can be seen as a precursor of the proxy voice. The growing popularity of ventriloquist shows in the mid-twentieth century can be attributed, at least in part, to the advent of radio . Never mind that the virtuoso animation of the dummy by the imperceptible vocal emission of its master was invisible to the audience; surprisingly, the credulity of the listeners was reinforced by the medium of radio, thanks to a double illusion: that of a voice twice dissociated from its body. Today, the use of delegated voices, which extends to the use of deep vocal fakes, serves to accentuate this detachment. In all fields, they generalise the agentivity of the artefacts of enunciation, communication and dissemination of discourse, in which the “first person” is ultimately untraceable.

The Sonic Web

On the global internet, images, texts and sounds are disseminated at an astonishingly rapid pace, so much so that their value is now gauged by the velocity at which they are transmitted . Virtual space can in effect be seen as a dynamic reservoir of data in which new approaches to creativity are emerging in response to the vast and ever-changing flow of information. In this section, the artist duo of Holly Herndon and Mathew Dryhurst, along with Tao Hui and Molly Soda, develop distinctive forms of writing from this seemingly inexhaustible material. Herndon and Dryhurst’s digital animation creates an unsettling visual journey, revealing how the process of translation between the audible/readable and the visible can be orchestrated using generative artificial intelligence. Tao Hui’s audio-visual installation takes a rather tender look at the eclectic and abundant musical culture that flourishes on social networks. Using an opera singer as a lunar witness to a cut-up of music videos sourced from TikTok, the artist reflects on the disruption of our sense of intimacy. Molly Soda’s video collage evokes the loss of the original, erased by the culture of cover versions in music. Designed to merge anonymously with online content, her work transcends the narcissism that characterises the internet’s virtual community.

These works are not simply creative investigations into the heart of a new reality as imposed by contemporary “screenology”. Rather, they examine and anticipate the epistemological rupture that this new reality is making with pre-existing systems of authorship and intellectual property, with values of rarity and authenticity, and with the very form and organisation of the meaningful and the intelligible.

While big data and deep learning have brought about a revolution in the role that digital technologies play in our environment, generative artificial intelligence is powerfully implementing a constant and pervasive automation in which all representations are compelled to merge into new amalgams without limit. It is evident that echoing this state of the world, sound – which can be described as a “liquid” medium –has once again become a privileged object of research among artists and in academic and musical circles . The field of sound practices encompasses a range of artistic strategies, including sharing, disseminating, reworking, interpreting and hybridising, and their potential is constantly being rethought and expanded. By definition, they create a space for dialectical play in which the immateriality of vibrational phenomena meets and negotiates the shifting materiality of the conditions of their audibility. This exhibition, attentive to the plurality of directions observed in recent years, aims to sketch an open score. It proposes to build a bridge between the pioneering experiments of the last century and the new configurations of forms and ideas that artists are now addressing to contemporary society.

- Read more about Open Score: Listening to an Exhibition

- Log in or register to post comments

I Never Dream Otherwise than Awake Journeys in Sound

Exhibition catalogue

First venue: Centre Pompidou x West Bund Museum Project

April 24 – September 30, 2024

Abstract

Relying on the New Media Art Collection from the Musée national d’art moderne – Centre Pompidou, in dialogue with young Chinese artists, this exhibition explores how sonic material has inspired new artistic thoughts and experimentations in the 21st Century. The mobility and impermanence of sound has long interested artists and musicians alike as a counter-model to the regime of the visual arts. Techniques of improvisation, collective practices, sampling and collage, feedback and filtering, phasing and spacing… the infinite plasticity of sound and the many ways in which it circulates continues to question our relation to the here and now.

The title of this exhibition is borrowed from its opening work: an immersive environment by Emmanuel Lagarrigue, which addresses a liminal space between wakefulness and sleep, a zone where aural experiences may emerge with a more intense quality. Coming from various continents and cultural contexts, the 24 artists here presented explore the unexpected dimensions of sound through a wide range of innovative strategies. Outdoors and indoors, the exhibition sets a series of encounters that manifest the power and agency of sound within the phenomenology of ambient space, within our senses and our imaginaries, within our social constructs and our relationships.

Along with contemporary art works, a few historical references allow an understanding of the fascinating history of sound as a source of displacement and estrangement of the ordinary.

With Francis Alÿs, Oliver Beer, Wang Changcun, Liu Chuang, Edmond Couchot, Mat Dryhurst, Kit Fitzgerald, Bill Fontana, Lucy Gunning, Holly Herndon, Gary Hill, Tao Hui, Hassan Khan, Emmanuel Lagarrigue, Anne Le Troter, Mark Leckey, Yuko Mohri, Emeka Ogboh, Susan Philipsz, John Sanborn, Molly Soda, Zhou Tao, Naama Tsabar, Sun Wei, Ye Hui, and Samson Young.

Book content

- Introduction on the exhibition by Marcella Lista (21,000 characters)

- Introduction on the music programs by Nicolas Ballet (15,000 characters)

- Twenty-four notices by Nicolas Ballet, Philippe Bettinelli, Julie Champion, Amy Cheng, Sylvie Douala-Bell, Bastien Gallet, and Marcella Lista (36,000 characters).

- 50 to 60 illustrations (photographs of artworks and views of the exhibition).

Notices

Nicolas Ballet

- Kit Fitzgerald, John Sanborn, Ear to the Ground, 1981-1982

- Hui Ye, It was so quiet that the pins dropped could be heard…, 2011

- Mark Leckey, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999

- Tao Hui, Pulsating Atom, 2019

- Sun Wei, Sound Temple, 2021

Philippe Bettinelli (philippe.bettinelli@centrepompidou.fr)

- Edmond Couchot, Michel Bret, Les Pissenlits, 1990

- Naama Tsabar, Stranger, 2017

- Molly Soda, Me Singing Stay by Rihanna, 2018

- Anne Le Troter, Parler de loin ou bien se taire, 2019

Julie Champion-Lagadec (julilagadec@gmail.com)

- Lucy Gunning, The Horse Impressionists, 1996

Amy Cheng (amy@thecube.tw)

- Francis Alÿs, Duett, 1999

- Wang Changcun, TV Waterfall, 2014

- Hassan Khan, Jewel, 2010

Sylvie Douala-Bell (sylvie.douala-bell@centrepompidou.fr)

- Emmanuel Lagarrigue, I Never Dream Otherwise Than Awake, 2006

Bastien Gallet (bastiengallet@yahoo.fr)

- Bill Fontana, Silent Echoes in the Dachstein Glacier, 2024

- Susan Philipsz, The Cuckoo’s Nest, 2011

- Emeka Ogboh, Conductors/ Oshodi Oke, 2018

Marcella Lista

- Zhou Tao, Chick speaks to duck, Pig speaks to dog, 2005

- Yuko Mohri, Parade, 2011-2017

- Samson Young, Muted Situations #22: Muted Tchaikovsky 5th, 2018

- Gary Hill, Full Circle, 1978

- Liu Chuang, Gluttonous Me, 2018

- Holly Herndon, Mat Dryhurst, I’m Here 17.12.2022 5 :44, 2023

- Oliver Beer, Reanimation 1 (Snow White), 2014

- Read more about I Never Dream Otherwise than Awake Journeys in Sound

- Log in or register to post comments

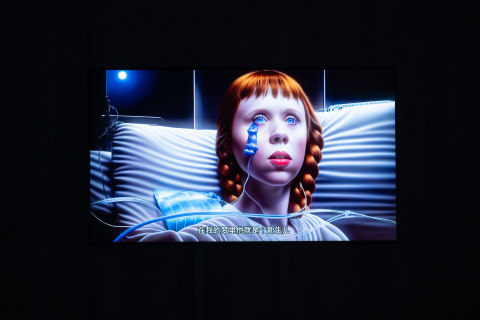

<I'm here 17.12.2022 5:44>

Holly Herndon, a composer, artist and musician who has gained considerable recognition beyond the art world, has been working with artist and technology researcher Mathew Dryhurst since 2013. Their joint projects investigate the potential of digital tools to facilitate new forms of collaboration, prompting a reassessment of the role of automated surveillance and artificial intelligence in the most intimate aspects of contemporary life. The defence of a decentralised internet that challenges the limits of copyright and the very idea of artistic property has informed much of their recent work. Holly + (2021), for example, devised a protocol for sharing Herndon’s voice – synthesised in the form of a fully functional deepfake twin – which could then be used by other artists to create their own musical compositions.

Herndon and Dryhurst were among the first artists to utilise generative AI tools, particularly text-to-image generators, to conceive visual works. I'm here 17.12.2022 5:44 was composed after a difficult personal ordeal – Herndon’s coma following the birth of their child, Link. The narrative of this intense experience, recorded in the days following her awakening, serves as a voice-over and introduces the prompt-driven generation of a series of images that were later reworked into an animation. Erratic and discontinuous, the visual sequence creates an unexpected, highly contrasting dialogue with Herndon’s emotionally charged narrative, at times anticipating her words and at others bouncing off her voice. The artists also illustrate the many faces of image generation, sometimes blurry, sometimes hyper-realistic, which can produce an infinite number of variations from a single textual source. While AI generators rely on the ever-changing data landscape of the internet, in this work Herndon and Dryhurst use them to develop a complex and deliberately unstable form of writing that reveals the vulnerability of memory, the shifting boundaries of the self and the unsettling visual intensity of artificial creation.

M.L.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Musée national d'art moderne / Centre de création industrielle (Mnam / Cci)

AM 2023-804